Every republic has founding quarrels. India has Nehru, Gandhi, and Ambedkar arguing over whether the new state would be socialist, village-centered, or liberal-constitutional. Pakistan has Iqbal and Jinnah wrestling with what it means to build a Muslim homeland out of the wreckage of the Raj. South Africa has Mandela and the ANC leadership negotiating, under the gaze of the old security state and with the memory of Biko hovering over the room, what a post-apartheid constitution should guarantee and what it cannot yet touch. Across Latin America, the transitions out of military rule and the new constitutions of the 1980s and 1990s posed the same question in different accents: how far to curb markets, the generals, and the old oligarchies without igniting a counterrevolution.

In the United States, we can name three such moments without much effort. The First Republic is born from Madison, Hamilton, and the Anti-Federalists arguing over the reach of the new federal government. The Second emerges from Lincoln, Douglass, Sumner, and Stevens fighting over slavery and Reconstruction. The Third is the New Deal order of Roosevelt, Frances Perkins, Walter Reuther, and Southern barons battling over the mass-party welfare state that remade capitalism without abolishing it. Their disagreements over federal power, race, and markets still structure our politics.

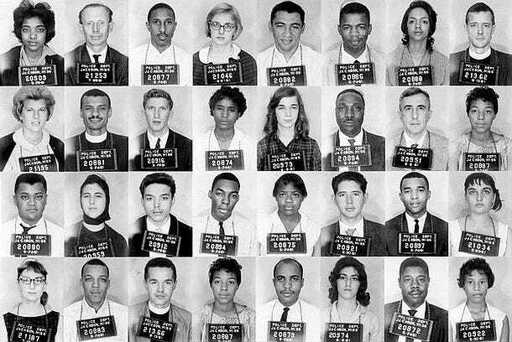

What we lack is a comparable language, and an equivalent cast of founders, for the Fourth American Republic: the constitutional order created when Black Americans forced the United States to dismantle de jure apartheid and finally extend formal citizenship across the color line. Between Brown v. Board and the Voting Rights Act, the country became, on paper, a multiracial democracy layered onto the New Deal’s economic regime. Yet the people who argued most intensely about what that democracy should be are rarely treated as framers. They are remembered as “civil-rights leaders,” not as architects of a new order.

This matters because the arguments we now conduct under the heading “the crisis of liberalism” are downstream of that unfinished founding. Jerusalem Demsas reaches back to Locke and Shklar to ask what liberalism is for: how a diverse society lives together without turning politics into permanent retribution. Matthew Yglesias looks at the institutional language of contemporary anti-racism and hears an illiberal turn: groups displacing individuals, neutral rules and objectivity treated as domination, universal rights and due process treated as obstacles. My own response has been that much of what he calls “postliberal” is not an external invasion but liberalism’s own cramped, elite offspring: a professional style that promises recognition inside institutions while leaving the political economy largely intact. Those are contemporary arguments, but they are not necessarily new arguments. They are, in softened and professionalized form, the arguments that forged and divided the founding generation of the Fourth Republic.

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was the crucible where many of those fights were conducted. SNCC’s organizers—John Lewis, Stokely Carmichael, Bob Moses, Ella Baker, Diane Nash, Fannie Lou Hamer, James Forman—and allied figures like Bayard Rustin and Martin Luther King Jr. fought over the meaning of American liberalism, the role of racism and capitalism, and the future of the Democratic Party. Their debates, as Founding Fathers and Mothers of a new republic, set the terms of the settlement that followed. Their breakup left unresolved tensions that still shape what counts as “liberal,” what counts as “identity politics,” and the Democratic Party.